[ad_1]

The Australia Letter is a weekly newsletter from our Australia bureau. Sign up to get it by email. This week’s issue is written by Natasha Frost, a reporter based in Melbourne.

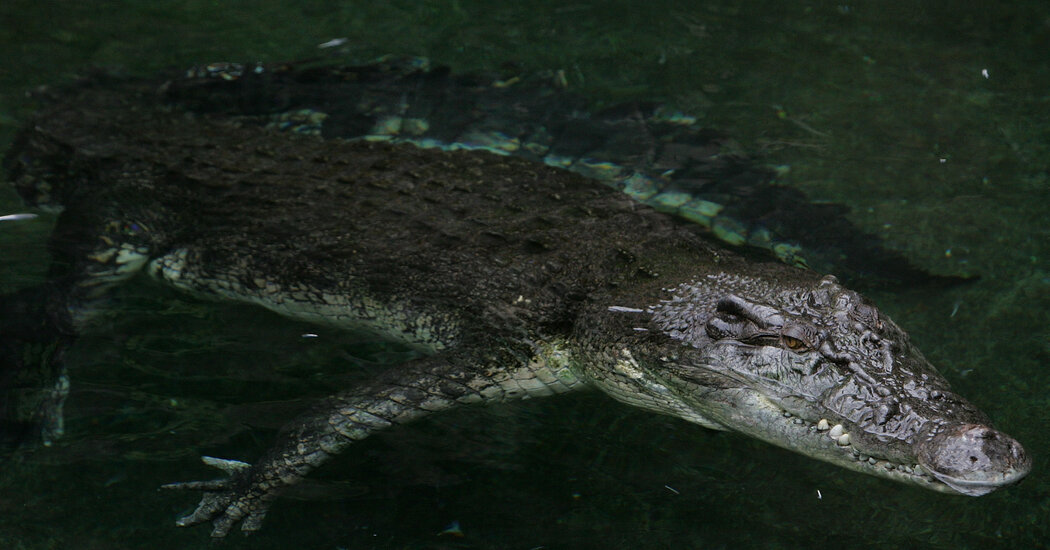

It was a story that seemed almost too Australian to be true: The incredible tale of a crocodile attack, foiled by the gnashing of the victim’s jaws.

Around a month ago, Colin Deveraux, a cattle producer from the Northern Territory, was working near the Finniss River, south of Darwin, when he was attacked by a 10-foot saltwater crocodile.

“I took two steps,” and the animal, he told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation this week, latched onto his right foot. “And it shook me, right away — shook me like a rag doll.”

A struggle ensued, with the crocodile attempting to pull Deveraux into the billabong, while Deveraux in turn, he said, tried to kick the creature with his left foot. He was pulled deeper into the water and onto his knees.

Then, in a move he described as “half-accidental,” his teeth caught on the animal’s leathery eyelid. “I managed to have a bite,” he said, adding: “I jerked back on his eyelid and he let go.”

It was “all reflex in the moment basically,” said Shane Thornton, his brother-in-law, in a message, “and probably something he may have rehearsed in his mind many times just in case, given the working environment.”

Deveraux was able to escape the creature, who chased him for some feet before stopping, and hotfoot it to his car. (Crocodiles, while they can move very quickly, cannot travel long distances on land before lactic acid begins to build up in their muscles.) His brother then drove him some 80 miles to the nearest hospital, where he has been for the last several weeks.

Deveraux, who is still recovering but who has retained the use of all of his toes, was not available for comment.

What should you do if you encounter a crocodile?

Brandon Sideau, a crocodile management expert who keeps a database of more than 8,000 crocodile attacks, does not recommend biting as a first call of action — though, he said, it had worked on a handful of other occasions, often in Africa.

“They’re not clean animals,” he said. “That’s a good way to get a stomach virus.”

The best tactic, he said, was steering well clear of dangerous water, particularly in areas like the Northern Territory, where crocodiles are common.

“Never go into a water body unless you know 100 percent that crocodiles are not in it, because a five-meter saltwater crocodile can remain completely hidden in fairly shallow water without making a sound or movement for three hours,” he said. “All they would need to do is just slip their snout out for a little bit, to get air, and then go under for another three hours.”

But in cases where that advice no longer applied, he said, three approaches worked particularly well.

“The most commonly used tactic for survival is gouging the eyes of the crocodile. That will, in many cases, result in the crocodile letting go of the victim,” Sideau said. “The second most common one I see is punching the snout, which sometimes will make them let go.”

Finally, he said, “if the croc’s got your arm, you can somehow get it down the crocodile’s throat and kind of gag it, to make you release you. It’s kind of a last-ditch effort — but you could also lose your arm in the process.”

All that was irrelevant for those few crocodiles that were more than 13 feet long, he added. “If you’re in the water, you’re not going to survive.”

Now for the week’s stories.

Are you enjoying our Australia bureau dispatches?

Tell us what you think at NYTAustralia@nytimes.com.

Like this email?

Forward it to your friends (they could use a little fresh perspective, right?) and let them know they can sign up here.

Enjoying the Australia Letter? Sign up here or forward to a friend.

[ad_2]

Source link