[ad_1]

Last year, the annual United Nations climate talks ended with a landmark agreement to compensate poor countries for destruction from climate disasters that have been made worse by emissions from wealthy nations.

Almost none of the details behind the so-called loss and damage fund were finalized, including which countries and financial institutions would contribute, and where the money would go. But last weekend, some of the key provisions were hashed out at a meeting in Abu Dhabi.

Under the agreement, the fund would launch next year, initially housed at the World Bank, and developing countries would have a seat on its board. Global leaders will be asked to ratify the plan at the United Nations climate talks known as COP28, which start later this month in Dubai.

The agreement marks a pivot point in the long quest to get rich countries, which have burned most of the fossil fuels that have warmed the planet, to help the poor countries that bear the least culpability but will suffer the most from climate change.

“We’ve been debating loss and damage for a long time,” said Avinash Persaud, a climate adviser to the prime minister of Barbados, who represented Caribbean nations in the talks. “This was a crunch point where we got together and said ‘Yes we will create a fund, yes we will help countries recover and rebuild.’ It was an important step forward.”

While the agreement can be seen as progress for climate diplomacy, the torturous process lays bare some of the tensions that are likely to shape the debate at COP28.

An unsatisfying deal

There was almost no loss and damage fund at all.

An effort to hash out the details of the fund last month in Aswan, Egypt, failed when negotiators hit an impasse. That forced countries to reconvene at last weekend’s emergency meeting in Abu Dhabi.

The negotiations were tense, with developing countries pushing for more concrete commitments and more specific language, and rich countries, including the United States, trying to keep the final agreement noncommittal. The U.S. unsuccessfully tried to insert language that said contributions to the fund would be voluntary.

“I don’t think anybody got everything they wanted,” Mr. Persaud said.

The initial target size for the fund is expected to be $500 million. That is a significant sum, but a pittance compared to the trillions of dollars that would be needed to pay for large-scale climate disasters in the years to come.

The U.S. delegation ultimately signed on to the final agreement, but immediately undercut it with comments that called into question its commitment.

“We regret that the text does not reflect consensus concerning the need for clarity on the voluntary nature of contributions; any contributions to funding arrangements, including to a fund, are on a purely voluntary basis,” the State Department said.

The fund will be housed at the World Bank, which is leaning into its climate work under new president Ajay Banga. But there is still deep-rooted skepticism about the bank, which is largely controlled by developed countries, especially the United States, and has a long history of saddling poor countries with debt.

Ann Harrison, the climate adviser for Amnesty International, flatly said: “it should not be run by the World Bank.”

But even though many were dissatisfied with the deal, the alternative was even worse.

“If we failed, it would have broken the COP,” Mr. Persaud said. “It would not have been at all tenable to say we are going to push developing countries to do mitigation, we’re going to push developing countries to be investing more in adaptation, but we don’t really care too much about loss and damages.”

‘Multilateralism is alive’

All of these tensions will be on display in Dubai later this month.

Many developing countries are tired of being told to reduce their emissions at the expense of desperately needed economic growth. And they are still waiting for hundreds of billions of dollars in financing, to shift to clean energy and build protections against climate change, that wealthier countries promised more than a decade ago, but have never fully delivered.

Rich nations are wary of accepting responsibility for climate damages, fearful that they could face unlimited liability. And while the United States and other industrialized countries are increasing their use of renewable energy, they continue to expand their fossil fuel production.

Nevertheless, the agreement to keep the loss and damage fund moving forward suggests that international community is still capable of working together on efforts to adapt to a rapidly warming world, if just barely.

“Multilateralism is alive, maybe weakly so, but it is alive,” Mr. Persaud said. “It is not dead. It can still deliver positive momentum. And so we go into COP with that behind us.”

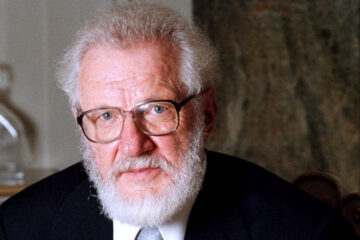

Related: Saleemul Huq, a widely respected Bangladeshi-British scientist who played a leading role in trying to get rich nations to compensate developing countries for the damaging effects of climate change, died on Oct. 28 at age 71.

A climate success story

Hoboken, N.J., is a water magnet. Most of the city occupies a flood plain along the Hudson River. Some scientists have forecast that, with rising seas, a big chunk of Hoboken will be Atlantis by 2100.

But for more than a decade this city of some 60,000 residents has been trying to thwart fate — and it is making progress, Michael Kimmelman, the Times architecture critic, writes. It’s elevating power lines, building cisterns and new sewers and redesigning to cope with rising seas and more intense rainfall.

In September, when a powerful storm hit the region, Hoboken easily handled the deluge.

New York City, on the other hand, ground to a halt, in a major signal that the city is not prepared for what’s to come. My colleague Winston Choi-Schagrin reported on the 100,000 New Yorkers living in coastal neighborhoods, who are already suffering from chronic “sunny day” flooding during high tides.

About half of them reside in the working- and middle-class enclaves surrounding Jamaica Bay.

“I think we’re doing the right things, but I think the challenge we face is whether we are able to do them fast enough,” Rohit Aggarwala, the commissioner of the city’s Department of Environmental Protection, told Winston. “Some of it is just how many resources can the city throw at these things in an environment of constrained budgets.”

As Michael wrote, cities will flood. The real measure of preparedness will be how well they can prepare, and how fast they can bounce back.

—Manuela Andreoni

Other climate news

-

Lavish tax credits and trade protections are finally reversing a long decline in solar manufacturing in the United States.

-

Extreme weather is helping invasive species, a new study found.

-

In keeping with tradition, King Charles III, a vocal climate advocate, gave a speech to Parliament outlining the priorities of the prime minister which include, this year, more fossil fuel extraction.

-

Electric school buses, which have big batteries and spend much of the day parked, may help utilities store solar and wind energy to prevent blackouts.

-

An electric plane’s test voyage from Vermont to Florida may foreshadow a new era of battery-powered air travel.

-

Nigeria’s decision to end fuel subsidies is kick-starting solar energy projects to replace dirty diesel generators, Bloomberg reports.

-

Facing setbacks for wind farms, the Biden administration said clean energy projects were still on track to meet its goals for 2025.

-

Offshore oil has made tiny Guyana the world’s fastest-growing economy, but some locals fear their country is becoming a subsidiary of Exxon, The Wall Street Journal reports.

-

Rich countries have signed a series of deals with emerging economies to help them switch from coal to clean energy, but early stumbles show the process won’t be easy, Grist reports.

[ad_2]

Source link